Building Digital Cities and Nations

Building Digital Cities and Nations in the Age of Data

Dissertation for Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Doctoral Degree in Political Economy of Urban Development, MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (2024)

Building Digital Cities and Nations

The idea of the “smart city” became a popular buzzword since companies like Cisco, IBM, and Siemens began promoting it in the early 2010s. The concept has been widely critiqued as a form of “techno-managerial” governance that reduces citizen agency in favor of control by technical experts and privileges corporate technological solutions over political processes,5 and are “deeply rooted in seductive and normative visions of the future where digital technology stands as the primary driver for change.”6 These critiques echoed Graham and Marvin’s warning about the “splintering” effects of digital infrastructure as previously public infrastructures became unbundled and repackaged as private networks or services. According to Greenfield, “the smart city is predicated on, indeed difficult to imagine outside of a neoliberal political economy.” 8 However, the smart city has more recently been embraced not simply as a corporate project but increasingly as an “imaginary” of national development. Despite the souring on the “smart city” among academics and public officials in the West, the term has lingered on as a zombie concept, finding new life in other parts of the world, and morphing from a simple corporate marketing effort to sell cities expensive digital infrastructures and control centers to a broader program of national development marshalling resources of nations, cities, and citizens in new and complex ways.

The City as Showroom

Xi Jinping and top advisors visit Xiong’an New Area, a key urban project personally championed by Xi.

In this chapter, I discuss how the countries in this book (Singapore, Thailand, and China) embraced “smart cities” and “cyber-physical” integration as part of their national development strategies. The 4th industrial revolution (4th IR) referred to a supposed package of revolutionary technologies that were to result from the further embedding of digital technologies in objects and the physical environment. Building on core insights of science and technology studies (STS), this chapter is concerned with how and why the concept of the 4th IR and its composite technologies resonated in these countries, all of which can be considered as variations of authoritarian or one-party states. In each of these contexts, the concept of cyber-physical integration was not merely a borrowing of foreign ideas, but resonated with existing institutional and historical approaches to development including a need on the part of state elites to showcase and display advanced technologies for public view and dissemination of new ideas. This chapter explores how cities function as political and ideological communication devices within political systems that are all variations of “one party” rule. The contemporary projects detailed in this book, like their historical antecedents, were built and designed by political or business elites with the intention to communicate ideal visions of technological and political orders from higher-level political leaders to lower ones. Thus, the projects were imagined not only as technological solutions to development problems, but as political and ideological communication devices: reinforcing national identity, offering visions of indigenous technological futures, and communicating ideals of governance to other leaders in each country.

Singapore: The City as Showroom

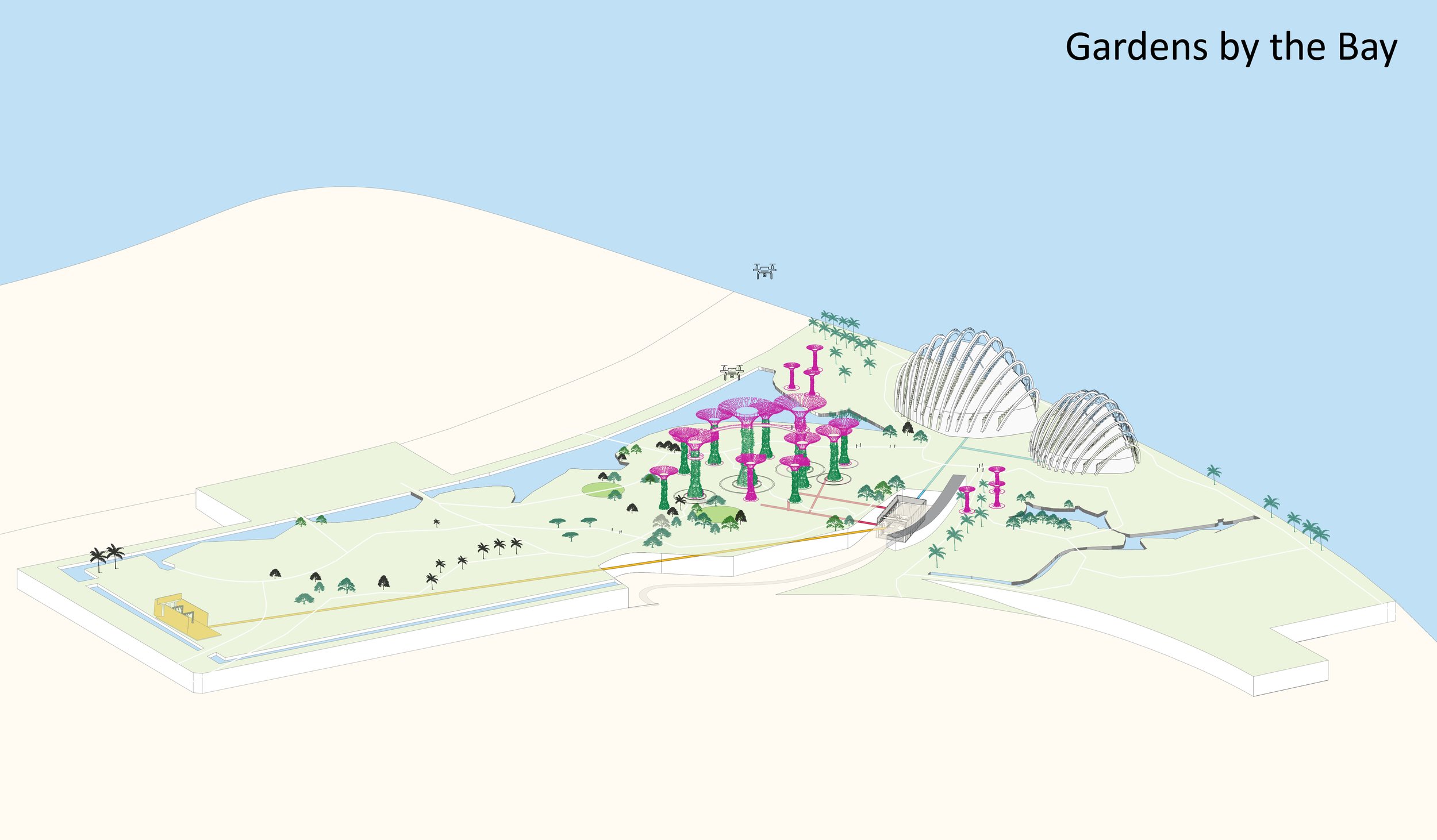

Today, the Gardens by the Bay are not only a tourist attraction and symbol of Singapore but also a testbed for new technologies of Singapore’s “urban solutions sector”. Whereas the colonial-era Botanic Gardens was a testbed for new plants the British hoped to cultivate for economic production across their colonies in Southeast Asia, today Gardens by the Bay is a testbed for new green technologies being developed as part of Singapore’s push to become a “smart nation.” Gardens by the Bay is perhaps the most iconic but not the only such testbed for technology within Singapore. In this chapter, I explore how various districts within Singapore have become testbeds for urban technologies, many as part of the Smart Nation Project. These projects serve as “showcases” in multiple senses of the word—for example, (i.) symbolically the Gardens are showcases of Singapore’s identity as a “City in a Garden”, (ii.) a showcase for new technology developed under the aegis of government initiatives like the Smart Nation, (iii.) showcases for the senior managers of Singapore’s agencies, and (iv.) a showcase for Singaporean companies looking to deploy their new products in high-profile settings, often with the goal of exporting that technology internationally. This is an imperative for most Singaporean companies, given the island’s small market size. And while many of the showcase projects within Singapore are developed by government agencies also known as “statutory boards”, related technologies are often then exported abroad by commercially-oriented infrastructure firms, most of which are owned by Temasek, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund. Because of the importance of the “urban solutions” sector to Singapore’s economy, certain districts and sites are effectively remade into testbeds and showcases for those solutions. Collectively the city has become a showroom.

Singapore’s Gardens by the Bay is a Showroom space, representing imaginaries of Singapore as a futuristic ‘Garden City’ (Author, 2024)

Thailand: Smart City in a Contested Polity

This chapter discusses the ways in which the smart city concept has been operationalized by a variety of actors in Thailand, beginning with a national-led effort through the Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA) to develop “smart cities” through piloting urban data platforms, then following several other cases of digital platforms promoted by entrepreneurial local businessmen, state-owned enterprises, mayors and governors. The current initiative on “smart cities” was disseminated as part of national economic policy (Thailand 4.0) formulated in 2016 after the 2014 coup. But the implementation of digital platforms shows how the concept has been seized on by a range of stakeholders to promote multifaceted uses of urban data platforms, each with a different vision for how urban data should be used to deliver benefits for cities. At the heart of this chapter is a question of who gets to own urban data and in (some cases) profit from the data, and who will realize benefits of the data. In his classic Imagined Communities, Anderson showed how mapping and visibility over territory through the map and census was an important tool of the power of modernizing nation states.[1] In Thailand, implementation of digital data platforms has direct implications for the contours of state “infrastructural power”[2]—data platforms are being used to bring greater state visibility over particular cities and regions, strengthen the tax collecting ability of local governments, and give local leaders a way to communicate directly with constituents and mobilize scarce resources to address urban problems. In the context of a highly unequal political and economic system that favors a Bangkok-based political and economic elite, some urban data platforms offer a new form of citizen voice in a political system where the results of popular elections have often been ignored or negated by military coups. At the same time, many of the data platforms are also being developed by state agencies and corporate conglomerates themselves. The outcome of urban data platform deployment does not depend entirely on the affordances of the platforms themselves, but on which configurations of actors and platforms come to profit from the extraction and use of Thailand’s urban data. This question is intrinsically linked to the contestation of state power between national agencies, economic and political elites, secondary cities, and citizens.

[1] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983).

[2] Mann, “The Autonomous Power of the State.” (1984)

A drawing of Wangchan Valley, a “smart natural innovation platform” developed in partnership between the state oil company PTT, EECi (the Eastern Economic Corridor of Innovation), and NSTDA, Thailand’s national science and research agency (Author, 2024)

Xiong’an and the Construction of a Digital China

This chapter examines the city of Xiong’an New Area as a lens into the construction of digital and ecological infrastructure as part of Xi Jinping’s vision of a “new development concept.” In general this involves moving away from market reforms and devolution of urban autonomy to a more centrally guided urbanization model involving greater role of central, provincial, and state-owned enterprises at the expense of urban autonomy. Following from the discussion of China’s national digital developmental policies in Chapters 2 and 3, this chapter focuses on the city of Xiong’an as a lens into how these efforts are playing out in a specific new city project. Xiong’an aims to be both “green” and a “smart city”, and ambitious efforts are underway to build digital infrastructure into the city from the ground up including an autonomous driving system, a digital twin of the city combining 3D models and 2D data with real time IoT sensors to facilitate both planning, design, and “operations” of the city in the future. Whereas private technology platforms like Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent have been active in developing smart city systems elsewhere in China, Xiong’an’s smart city development is being guided almost entirely by a consortia of state-owned telecom companies and infrastructure companies. This reflects Xi Jinping’s ongoing efforts to ensure control of data resources in the hands of the party state, and help build a “Digital China” a nationwide policy unveiled in 2023 that aims to deploy physical and digital infrastructure, boost digital governance, and leverage “data as a production factor,” a phrasing that suggests a reconceptualization of data as not merely an economic asset for private profit but also a critical resource for national development. Xiong’an, like some of the other cases in this project, is a national showcase: described in official media as a “national template” for “high quality development” the current favored term to describe China’s shift to a clean and innovative development model. Whether or not the city itself can be a model for other Chinese cities remains to be seen, but given the full backing and close personal investment of Xi Jinping, the “Xiong’an experiment” will likely have implications for the rest of the country.

Axonometric drawing of the Rongdong Area, the prototype district of Xiong’an New Area showing extensive Chinese-style landscaping, buildings, and data center (Author, 2024).

Street section of underground utility corridors (dixia guanlang), and digital infrastructure (5G, cameras, sensing equipment) in a typical Xiong’an street (Author, 2024)

Axonometric of the Xiong’an Cloud Supercomputing Center, the nerve center of the city’s digital infrastructure (Author, 2024).