Exploring Seoul's Urban Form

Looking at a city's urban form, or its general layout of physical features (streets, block sizes, buildings), can tell us a lot about a city: how it developed, how walkable it is, what era it dates from. In his book Great Streets, UC Berkeley urban design professor and former SF Director of City Planning Allan Jacobs compared various cities around the world by creating figure-ground diagrams of streets and blocks, white representing roads, black representing buildings or blocks.

Looking at a city's urban form, or its general layout of physical features (streets, block sizes, buildings), can tell us a lot about a city: how it developed, how walkable it is, what era it dates from. In his book Great Streets, UC Berkeley urban design professor and former SF Director of City Planning Allan Jacobs compared various cities around the world by creating figure-ground diagrams of streets and blocks, white representing roads, black representing buildings or blocks.

With these simple drawings, produced at the same scale (each square represents one square mile in each city) Jacobs shows the difference in block size, street width and general street layout between Cairo, Rome, and New York, pictured here, along with many others. We can clearly see a progression in organization and planning from Cairo, the streets of which are composed largely of small tiny alleys with a few broad boulevards, to New York, where every street is arranged in a strict grid as specified by the 1811 Commissioner's Plan that laid out Manhattan's grid. Rome's layout reflects the baroque ideals of Bernini and other Renaissance architects: plazas connected by boulevards that cut across the city's fabric.

What of Seoul? Its urban form has not been adequately studied although it is the word's second-largest metropolis after Tokyo, at around 25 million people. Below are several similar square-mile cutouts of Seoul's urban form from different parts of the city. Seoul presents great variety in street form—it is hard to say that there is a typical urban form, at least from analyzing blocks and streets at this scale. Seoul's rapid development meant that it did not have the luxury to be guided by an overarching urban vision as some cities. Rather, the city is composed of many different neighborhoods ranging from the Joseon capital that was made up mostly of traditional courtyard homes, hanok, to the modern district of Gangnam, with its broad boulevards and glass-paneled office towers. One can clearly see the progression in urban form as we move from the traditional city to the newer areas of Gangnam. I selected the following three neighborhoods because they are roughly representative of different eras in the city's history.

Jongno: the historic center

Jongno, at the left, is the city's traditional center—the double-laned boulevard running from the center of the image to the top is Gwanghwamun, the ceremonial axis that connects city hall to the front of Gyeongbokgung Palace. In addition to this street, there are also many smaller alleys still in existence that date from the Joseon Period (1392-1910). As Seoul's first business district, much of Jongno's historic fabric has been replaced by office towers, although there are pockets of the smaller alleyways that remain.

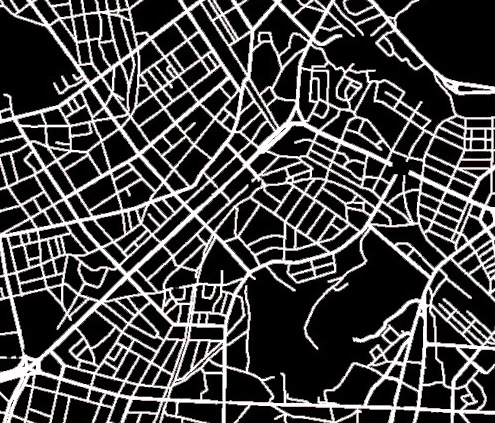

Hongdae/Sinchon: the student neighborhood

To the west of Jongno and the old city wall is Seoul's largest student district . The street network here is dense and varied: there is little discernible pattern. The main boulevard running through the center and to the bottom left corner is the main commercial corridor of the area, underneath which runs Subway line 2. This area, lying just outside the old city's west gate, Sodaemun, saw development of towns and suburbs even in the late Joseon period, but only became part of Seoul proper after World War II. Gradually, these small villages, including Sinchon (whose name means "new village") were stitched into the fabric of Seoul. Sinchon can be seen at the center right of this image.

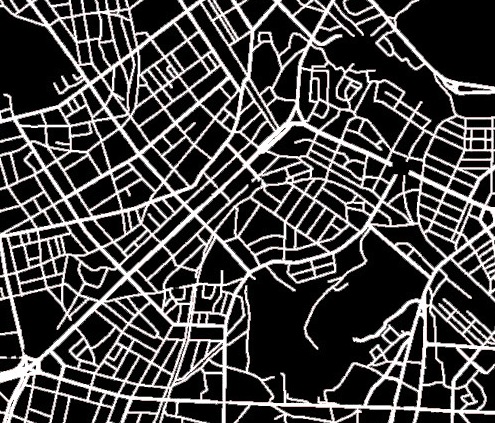

Gangnam: the modernist ideal

The third map shows Gangnam, now world famous because of a certain Psy song that you may or may not have heard of. This part of the city, lying south of the Han River (that's what Gangnam means), was developed in the 70's as a modern extension of Seoul and was heavily planned by the national government. This area, with its wider orthogonal streets and boulevards, comes closest to New York in its rationality and grid. However there is still a lot of variation in block size within it: larger blocks are apartment complexes designed in the modernist ideal separated from the street, while smaller blocks retain a more fine-grained urban fabric even amidst the tall business towers of Teheran-ro, one of the city's newest business districts. The large white line on the left is the Jungbu Expressway connecting Seoul with Busan, the completion of which marked the beginning of Gangnam's real estate boom. The main intersection in the upper part of the map is the Gangnam Station intersection.

Importance of Urban Form

Jacobs diagrams the urban form of world cities to show how scale impacts our experience of cities. Coarseness, characterized by broad streets and large blocks, generally leads to less walkable cities—we find coarse urban form in American suburbs and business parks, places like Houston and Los Angeles. Fine-grained urban form is characterized by small streets, often car-free, small blocks, and a high level of connectivity between streets. New York's grid, while quite dense, is not actually optimal in terms of walkability or connectivity: because the avenues running north-south are spaced far apart while the east-west streets are very close, you have long rectangular city blocks: perfect for building skyscrapers but not that great for walking. Seoul actually offers high connectivity because while there are only a few large boulevards, there are many smaller alleys that run parallel to them, offering alternative routes as well as pedestrian ways that are less heavily trafficked than the main boulevards.

References

Allan Jacobs, Great Streets. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993.